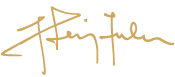

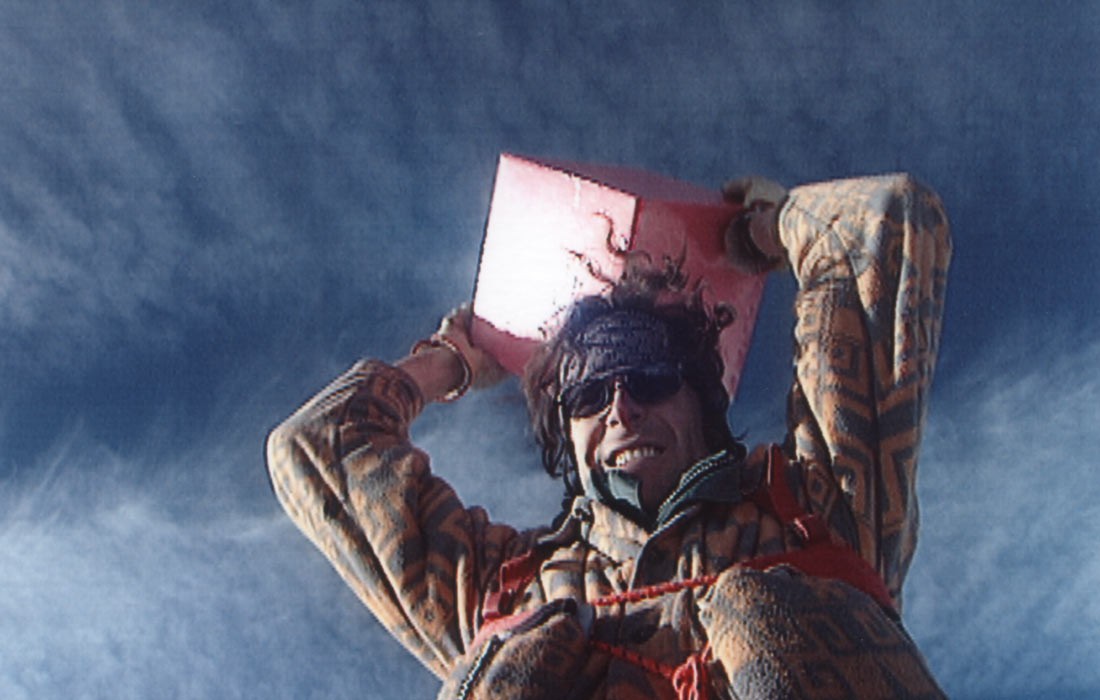

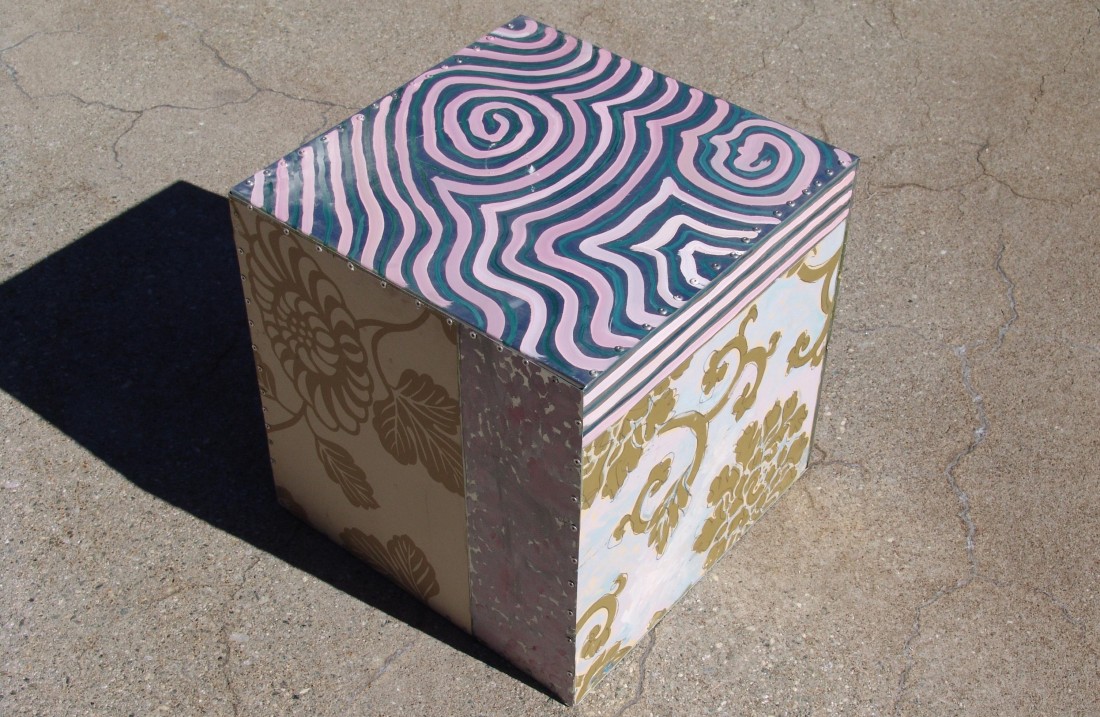

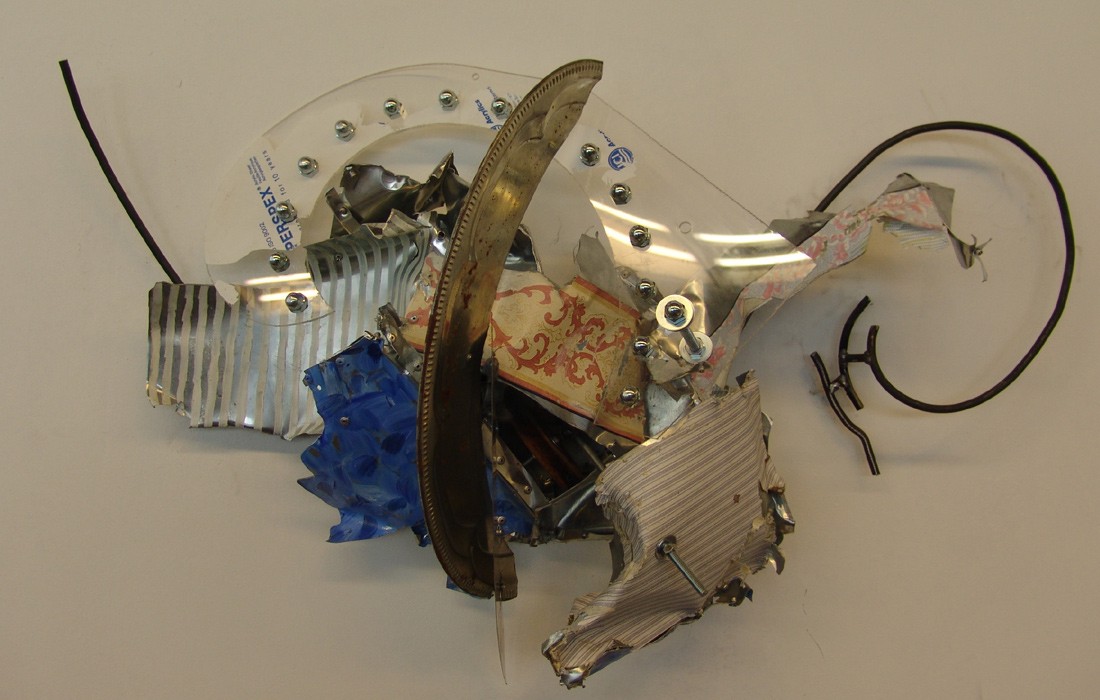

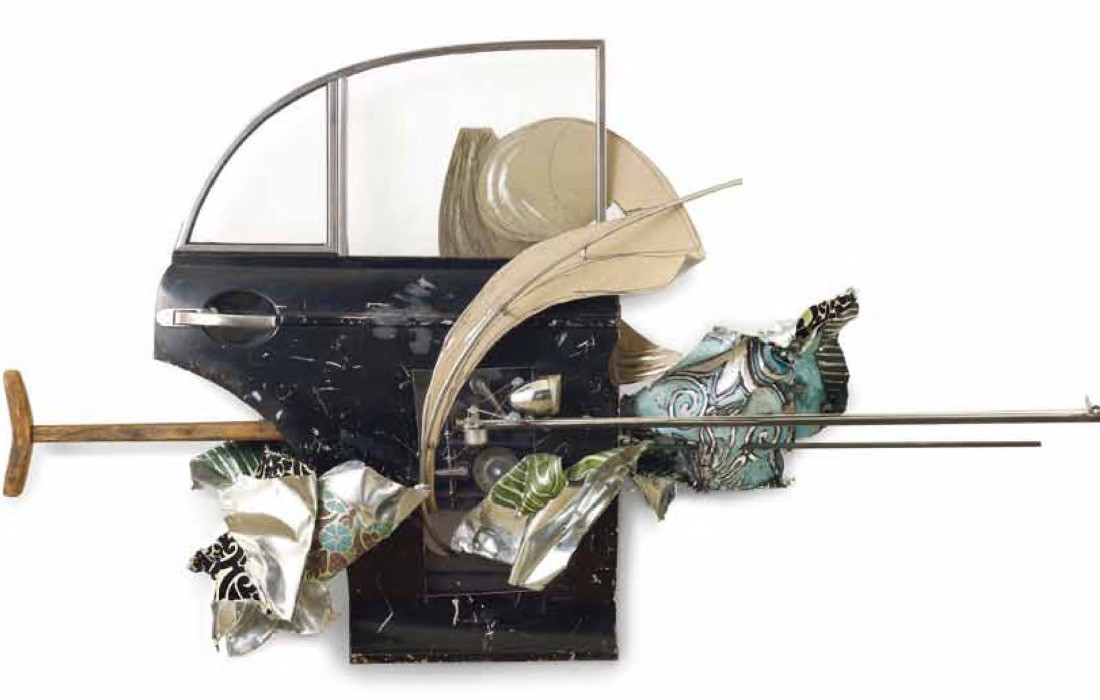

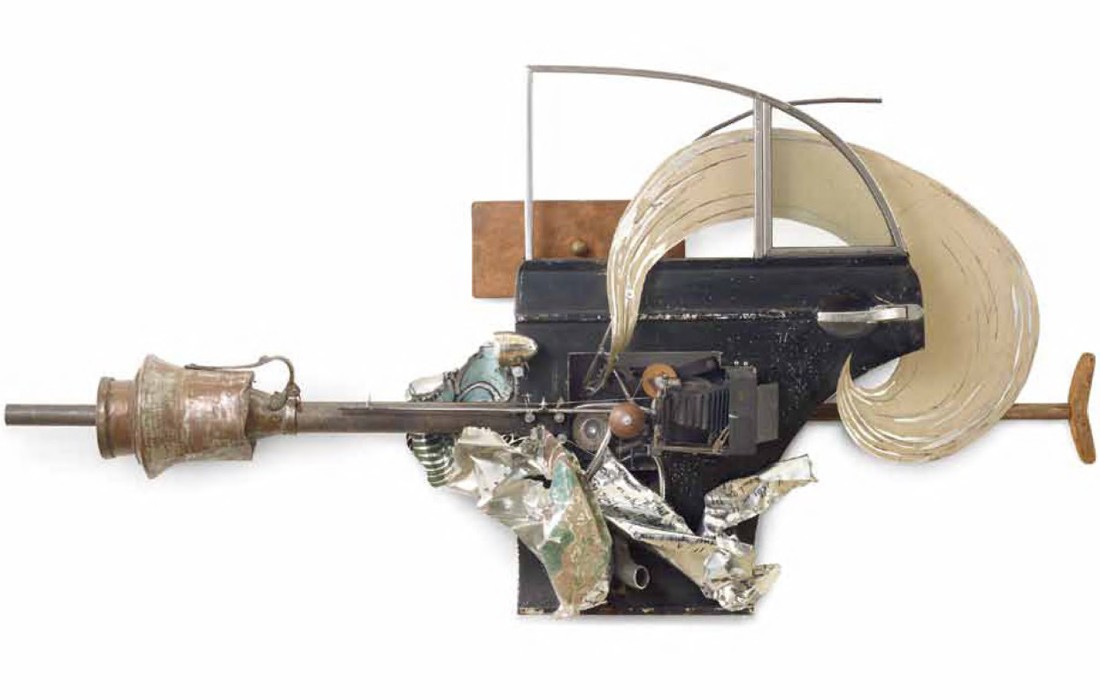

The WEILAND work is based on my first Mountain Cube projects from 1994. At that time, I was interested in an interpretation of the mountains. Instead of painting them, and thereby merely create a lacklustre image, I chose a different approach. I made cubes out of sheet metal (30 x 30 cm) and dropped them off various summits. I then collected them up again, placed them in Plexiglas boxes with a precise description of their fall, their flight through the air, where they were found, the time and place. This was all shown on topographical maps in scrupulously accurate detail (1). An abstract form was thereby created. The viewer visualises the fall of the mountain cube and the result raises hardly any questions at all. The abstraction convinces. For me, the throwing away of the cube creates an almost ecstatic state. By throwing it away, by releasing it, I withdraw my responsibility for the object. In doing this, I thereby compel it to take on a history, which arises during its fall, on its path. I then recover the object and make my interpretation of it. From my point of view, these works have a spiritual function and approach a truth that I have been seeking, a truth that is founded on religion and that has a symbolic meaning form: I am the God-Creator of the cube that I conceived and that I have now sent on its way, into its own life. On its path, it attains rough edges and dents that characterise its story, its life. Wouldn’t it be marvellous if the God-Creator who conceived us and threw us into our lives would one day draw us back to Himself at the end of our journey and then take us into his personal presence, into his collection? The thought alone is beautiful. The second (2) and third editions of the mountain cube were colourfully painted and weighted with stones before being dropped, so that the traces of their journey would be even more intensively marked. These works were inspired by the American Pop Art movement. We could hereby mention artists such as John Chamberlain or Frank Stella. The American thing about all of this is probably the performance itself, the action part of the fall, the drama, the sensation as a film, at the very least in the mind of the beholder. The fourth series of the Cube in the year 2002 was decoratively painted and glued together as a collage. The staging was no longer carried out. I was much more attracted by the transformation of a once-beautiful object that was now destroyed or changed, bringing it into a new form and thereby integrating its story: to fabricate a new world from the debris, which would continue to live in a new guise. From that point onwards, I called the series WEILAND (English: once), from something that used to be. Three-dimensional wall compositions, glued together, bonded and made up from broken individual parts, have thereby been composed from the broken parts. It may well be that this development could be traced back to my supposedly failed ‘Into the Hotel’ project from the year 2000, which, after its highly praised opening, was torn down again and destroyed seven weeks later for emotional reasons. I had to relive my existence, my work, from new out of this debris. The personal confrontation with this part of my life is best reflected by the fourth generation of the mountain cube, now known as WEILAND. Foreign and second-hand materials were incorporated in the fifth generation from the year 2011. The basis remained the richly decorated cube, however (this time somewhat bigger, at 50 x 50 cm), whos form and uniqueness relate to the almost 2,000 metre high North Face of the Matterhorn, and are thereby the basic inspiration. The optical fusion of the different objects and stories allows plenty of free room for the individual fantasy of the viewer. In a time of digital technology and a craze for functionality, these works appear simple, and their cosmos is easily understood. They could trigger playful, metaphysical thought. Or could they bring out the child in the viewer? That wouldbe great, and would close the circle to the spiritual dimension of the work with the words of Jesus, who said «Let the little children come to me, and do not hinder them, for it is to people like this that the new world of God is open.» Heinz Julen

Weiland is a very old german word.

It was employed to designate something that, at the beginning was fine and beautiful, which became damaged, because of the years or some other cause, and which recovered a second life and a new beauty. Weilands are a second generation of Bergwürfel. Here the cubes are shaped before and after their fall, the artist gives his interpretation of the creation of the mountain and chance.